If your ancestors were in Ireland in the early 20th century, the 1901 and 1911 Census returns are a great place to start your genealogical research.

While a census was taken in Ireland every 10 years from 1821 to 1911, the only complete census records which are publicly available are those from 1901 and 1911. When the time came to organise the 1921 Census, the country was two years into the War of Independence and, because of this, no census was taken that year.

The first census of the Irish Free State was undertaken in 1926, and this census will not be published until April 2026 under the 100-year rule.

So, while the 1901 and 1911 Censuses are important historical records in their own right, they are all the more precious because they are the only complete censuses that are publicly available to view.

Both censuses are available on the National Archives website.

The 1901 Census took place on 31 March 1901, while the 1911 Census took place almost exactly 10 years later on 2 April 1911. It is useful to think of these records as a snapshot of where people were on these dates – they may have moved around before, between, or after the Censuses were taken. This is particularly true for adult children living at home or boarding with relatives, as well as non-family members listed as boarders, visitors, etc.

So, what’s in the census records?

Household returns

Both censuses contain the details of people living in every household in the country. The head of each household was required to record details of the name, age, religion, birthplace, occupation, literacy level, languages spoken (Irish and/or English), and marital status of each person in the household.

Everyone recorded was also defined by their relation to the head of the household – for example wife, son, daughter, visitor, lodger, etc.

In the 1911 Census, married women were also required to detail how long they had been married, how many children were born, and how many were still living. This was the first record of infant mortality in the country. Widows were not required to fill out this section, but many did.

While these Censuses recorded the details of every person in the country, there are a few caveats. While the details of soldiers, policemen, and the inmates of workhouses, mental hospitals (as they were called in the language of the time), and other institutions were included, they were only identified by their initials.

The information on individuals was collated in the Household Return Form – Form A, and all of these returns are available to view on the National Archives site under ‘view census images’. It is worth clicking through to the forms to see your ancestor’s handwriting – each form was filled out, and signed, by the head of the household.

All of the fields in the Household Return Form are searchable – click on ‘More search options’ above the search form to access these.

This advanced search can be useful if you are struggling to find a specific person and know their marital status, birthplace, or religion. However, be aware that spelling could vary when it came to listing occupations.

You should also treat people’s ages with scepticism – birthdays were not celebrated in the early 20th century, and many people simply did not know their age. Because of this, recorded ages can vary wildly for the same person between 1901 and 1911.

As a general rule, the older someone was, the more likely their age was incorrect. While children’s ages are usually reliable, this is not always the case.

The enumerator’s abstract

The enumerator’s abstract provides a snapshot of every house in a townland or street. It contains information on the number of people in each household, broken down by sex and religion. It also includes details on unoccupied buildings.

The house and building return

The house and building return form can shed light on the conditions in which a family lived. It records the details of every building in the townland or street.

These details include the type of building – whether it was a house, shop, or other premises – the number of outbuildings, what type of walls and roof it had, how many front windows were present, and how many rooms were in the building.

This information is helpful when forming an idea of how the people in a house lived, and their economic circumstances. The most obvious details are how many people were living together, and how many rooms they shared.

Houses were also rated on a sliding scale as first, second, third, or fourth class. This classification was based on criteria such as whether the roof was slate or thatch, what the walls were made of (eg stone, brick, mud or wood), as well as the number of rooms and front windows.

The out-offices and farm steadings return

While the number of outbuildings associated with each house was recorded in the house and building return, this form listed details of what type of outbuildings came with the house.

The various outbuildings were generally for agricultural, industrial or domestic use. They were classified as stables, coach houses, harness rooms, cow houses, calf houses, dairies, piggeries, fowl houses, boiling houses, barns, turf houses, potato houses, workshops, sheds, stores, forges, and laundries.

The number, type, and/or absence of outbuildings help to shed further light on the economic circumstances of the family who lived in the attached house.

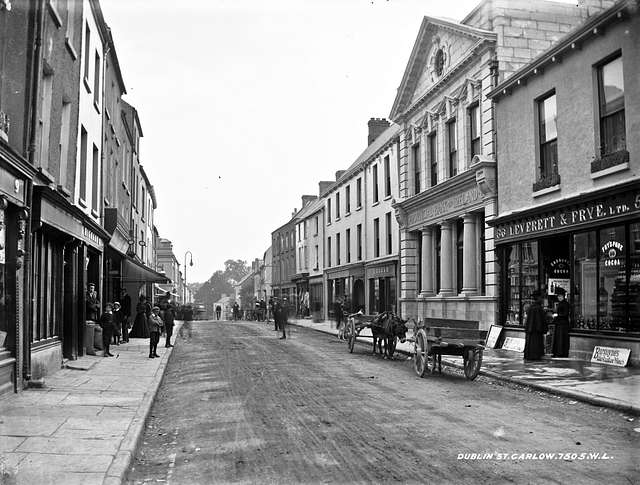

Featured image: Dublin Street, Carlow by Robert French, via National Library of Ireland/Picryl.

Una Sinnott

I love exploring how our ancestors lived, and what we can find out about them from the records they left behind. Get in touch if you need help researching your Irish roots.