Spanish flu was the first pandemic of the 20th century. It was also the most destructive, and one of the first to spread so rapidly across the world. Now, as COVID-19 does the same thing, the Great Flu of 1918 serves as a 100-year-old example of how a pandemic can paralyse societies.

When the flu struck Ireland, it decimated a country which was already experiencing significant upheaval. Many thousands of Irish men were away fighting in the Great War, and likely brought the disease home with them when they returned on leave. The pandemic also coincided with the War of Independence.

Like much of the rest of the world, Ireland experienced the pandemic in three waves, and saw unusually high mortality rates in otherwise young, healthy adults. Along with its sudden onset, this was one of the most frightening aspects of the disease — it struck down young men and women in their prime, and also killed and orphaned countless children.

In May 1918, just before the first flu cases were reported in Ireland, the country’s newspapers were busily focused on the progress of the Great War, with several titles speculating as to why the German army had reduced their activity on the Western Front. Amid rumours of mutiny among the troops, news of another reason was emerging.

“From medical sources it has also been ascertained that a very severe epidemic of influenza is now raging in the ranks of the German forces,” the Dublin-based Freeman’s Journal of 25 May 1918 reported.

The Germans were not the only troops suffering from the flu, though no mention was made of the impact of the epidemic on the Allied armies. However, according to the Kilkenny Moderator of 8 June, the flu was also “creating great public alarm” in Spain.

“In some respects the new disease is akin to influenza, but differs from that malady in that its victims in many cases are suddenly seized with fits while walking in the streets,” the newspaper stated.

The virus had by then affected an estimated 40 per cent of Spain’s population, according to reports, including King Alfonso XIII, the Prime Minister, and several government ministers. Commerce in the country had all but ground to halt in the face of the epidemic.

A Spanish flu?

Despite its popular name, the flu was not Spanish in origin. Unlike many other countries affected, Spain remained neutral throughout World War I, and as a result its media were more forthcoming in reporting the details of the pandemic.

As Dr Legroux of the Pasteur Institute, attempting to play down the severity of the pandemic, told the Northern Whig in June 1918: “The Spaniards made a great fuss about it; but for that it would not be noticed today.”

Though the first reports of the epidemic in 1918 came from a military camp in Kansas, USA, and a similar illness was reported among British troops as early as 1916, it is not known where the virus originated.

Many soldiers are believed to have brought the disease with them from the Western Front in France, giving rise to its somewhat less common name, Flanders flu. The movements of troops also helped the virus to spread rapidly between countries.

‘No grounds for alarm’

Just days after reports emerged of the calamity in Spain, an epidemic was under way in Belfast. Those afflicted showed several novel symptoms, and at least one factory — James Mackie & Sons, which made munitions — had to close due to the number of workers who had taken ill. Several soldiers were also infected, possibly before returning home from the front.

“The general signs include an intense headache, sudden faintness, feverishness, sore throat, pains in back, and a high temperature,” the Belfast Telegraph of 11 June revealed.

Despite the outbreak, the Telegraph stressed that there was no cause for concern.

“We have been asked to impress on the public that there is no ground whatever for alarm or even uneasiness,” the newspaper stated.

Within days an influenza epidemic was reported in Berlin. By then several schools in Belfast had closed as the infection spread, and three people in the city had died. As the first city in Ireland affected by the pandemic, Belfast was hit particularly hard.

By late June thousands of people in Belfast had been affected, and the city was going the same way as Madrid and Berlin, with factories and shipyards shut and tramways unable to operate due to the numbers of staff infected. Schools closed in Derry, to prevent children spreading the infection further.

The pandemic had also extended through the country, with outbreaks reported in Athlone, Ballinasloe, Dublin, and Tipperary town.

Towards the end of the month, Irish newspapers were reporting of an outbreak in northern China, where some 20,000 people had fallen ill.

‘Avoid crowded spaces’

According to the Portadown News of 29 June, the virus tended to infect children first, before spreading among the adults of a community. The article also offered some suggestions for both treating and avoiding infection:

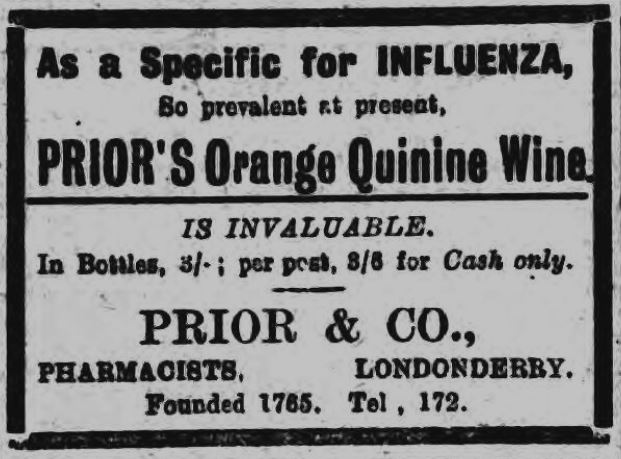

“When one is affected by influenza there is only one way of dealing with it,” it advised. “Go straight to bed and remain there until the attack has spent its force. Small doses of quinine, formamint, or cinnamon are said to be useful preventatives. But the best way to ward off an attack is to take plenty of exercise and fresh air and to avoid crowded spaces.”

The Freeman’s Journal of the same day also had advice on avoiding infection, courtesy of a Dr Niven from Manchester. “The sick should at once be separated from the healthy,” Dr Niven said. “This is especially important in the case of first attacks in a household, factory, or workshop.

“Discharges from the eyes and nose should not be allowed to get dry on a pocket handkerchief or inside the house or workshop. They should at once be collected in paper or clean rag and burned. If this cannot be done the paper or rag containing the discharges should be dropped into a vessel containing water.

“Infected articles and rooms should be cleaned or disinfected.

“Those attacked should not not on any account join assemblages of people for at least a period of 10 days from the commencement of the attack.

“Persons who are attacked by influenza should at once seek rest, warmth and medical treatment; and they should bear in mind that the risk of a relapse, with dangerous complications, constitutes a chief danger of the disease.”

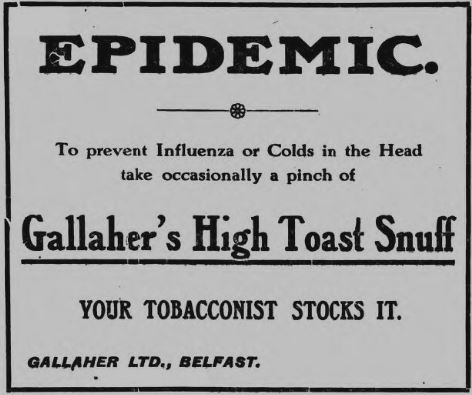

Measures to combat the epidemic in Belfast included a regime of disinfecting buildings and widespread use of quinine, the main medicine recommended for the illness. Dozens of people died in the city in June, due to either influenza or pneumonia, the latter most likely a complication of the flu.

‘Chemists besieged’

According to the Derry Journal of 26 June, doctors in Belfast were “kept busy day from morning to night, while chemists’ shops have been literally besieged by persons anxious to purchase the necessary medicines for friends attacked by the malady. Indeed, in one of the shops in the centre of the city a queue of people were observed during the early part of the day standing along the footpath waiting their turn to be served.”

In July, people continued to fall ill by the thousands in Belfast, where the warm, humid atmosphere of the city’s many linen workshops provided the perfect conditions for the virus to spread. When people greeted each other in the street, the most common salutation was, ‘How many are down in your house?’

By early July, Derry was reporting more funerals than at any point in the previous 30 years, presumably since the Russian flu pandemic of 1889/1890. In at least one case, an entire family died of influenza, including two young children aged eight and four, and their parents, over the course of a few weeks.

According to the Londonderry Sentinel of 9 July, 50 burials took place in the city cemetery in the first week of July, with 14 in one day the following week.

“A special staff of gravediggers had to be employed,” the newspaper reported. “In addition, during this period there was a considerable number of interments in the surrounding districts. Amongst those buried last week were two prospective brides, who were to have been married in a few days.”

Meanwhile, several people had collapsed in the street in Cork, and had to be hospitalised. Numerous businesses in Waterford had also seen outbreaks. Schools were closed in Drogheda and Dublin.

Shops in the capital were running short of quinine, while 60 cases were reported in one convent in the north of the city. Several Dublin doctors were no longer able to attend to the sick, as they had fallen ill themselves. Deaths in Belfast doubled during the first part of the month.

The end of the beginning

By mid July, newspapers were reporting that the epidemic was abating in Ireland, and life started to slowly return to normal. Though people were still contracting flu, resulting in closures and staff shortages in companies around the country, the numbers continued to decline.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1918, public buildings such as cinemas were disinfected daily in a bid to reduce the spread of the illness, and people were regularly warned to stay away from crowded places.

Though there was an awareness that the flu was caused by an infectious agent (the influenza virus would not be discovered until 1930), much of the blame for the illness was placed on the weather, dusty streets, and poor diet, with political prisoners in several prisons around the country calling for dietary improvements to protect them against the scourge.

As the summer and, by all accounts, the epidemic, drew to a close, the illness was ultimately put down to a particularly virulent seasonal influenza. But the Great Flu had not disappeared — Ireland had just experienced the first of three waves of the pandemic, and the worst of it was yet to come.

Una Sinnott

I love exploring how our ancestors lived, and what we can find out about them from the records they left behind. Get in touch if you need help researching your Irish roots.